Abstract

The cell surface antigen CD33 is expressed on the majority of AML blasts and is appropriate for immunotherapeutic targeting with antibody drug conjugates (ADCs). Expression of CD33 is in part mediated by splicing of the CD33 transcript, and has been demonstrated to be one of the factors that may mediate response to the ADC gemtuzumab ozogamicin, which results in significant benefit in some patients but lacks responses in others. Splicing of the CD33 transcript is in part regulated by a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in exon 2 (e2) that causes a C>T substitution and the resultant skipping of e2. CD33 thus exists in 2 main isoforms, as either a full length (FL) transcript or a truncated version missing e2 (Δe2), which includes the IgV binding domain that is the epitope for diagnostic and therapeutic antibodies (Ab). The CC genotype encodes the FL isoform at a higher rate compared to the CT or TT, and the TT genotype encodes the short isoform at a higher rate compared to CT or CC. SGN-CD33A is a CD33-directed ADC, utilizing a pyrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimer. SGN-CD33A has been evaluated in multiple clinical trials as either monotherapy or in combination. We hypothesized that the patient's CD33 genotype would impact CD33 expression as well as response characteristics following treatment with SGN-CD33A.

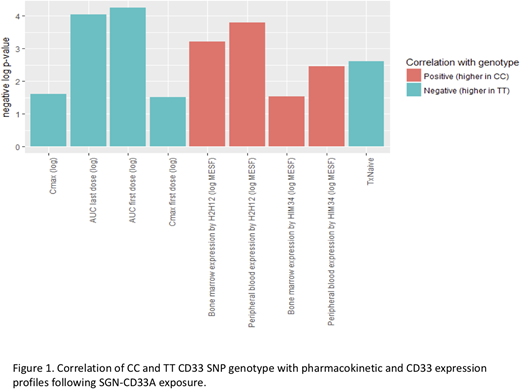

We analyzed CD33 genotype variation in bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blood (PB) samples from patients treated with SGN-33A as either monotherapy (NCT01902329; n=133) or in combination with hypomethylating agents (HMAs; NCT02785900; n=83). CD33 SNP genotyping was determined on gDNA using RFLP PCR with 2 restriction enzymes recognizing cut sites generated by the C and T polymorphisms and genotype confirmed using fragment length analysis (CC=108, CT=86, TT=22). CD33 surface expression on the AML blasts was determined by flow cytometric analysis using the human anti-CD33 monoclonal Abs HIM3-4 and H212, which bind to the membrane-proximal C2-set and V-set domain, respectively. HIM-34 measured CD33 levels independent of SNP-driven splice variation. The h2H12 epitope is within e2, thus its binding may be susceptible to splice variation. We subsequently evaluated the association of CD33 genotype with pharmacokinetic (PK), clinical and other variables using a generalized regression model.

Patients classified as CC genotype had significantly higher surface CD33 expression as determined by flow cytometry in both BM and PB. In accordance with observed differences in CD33 expression, we also found drug exposure demonstrated an inverse relationship according to CC genotype in both mono and combination therapy trials. For monotherapy, compared to patients with CC and CT genotypes, patients with TT genotypes had significantly higher drug exposure following SGN-CD33A. Patients with TT had higher AUCs following the first and last doses of SGN-33A (p < 10-4 -; Fig 1). Cmax following SGN-CD33A exposure was higher in TT genotype patients compared to the CT and CC (p< 10-1.5 for Cmax following the first dose and p<10-1.6 for Cmax over all treatments;Fig 1). In combination with HMAs, the TT genotype was also associated with significantly higher SGN-CD33A AUC and Cmax (p-values ranging from 10-3.3 - 10-9.7).

We next examined expression and subcellular localization of CD33 to elucidate the mechanism by CD33 variation contributes to cell surface presentation. Transfection of cDNA encoding the FL CD33 transcript resulted in increased cell surface expression, as indicated by flow cytometry with both HIM3-4 and h2H12. In contrast, both Abs failed to detect cell surface CD33 following transfection with cDNA encoding the Δe2 variant. Examination of the intracellular compartment revealed that HIM3-4, but not 2H12, binds to the Δe2 variant in a pattern localized proximal to the nucleus. Taken together, our findings suggest that the Δe2 splice CD33 variant lacks the portion of the V-set domain required for h2H12/SGN-CD33A binding and does not efficiently traffic to the cell surface. We show that CD33 SNP genotype is associated with CD33 expression, with CC patients demonstrating higher CD33 as detected by flow cytometry; and that CD33 SNP genotype affects the PK profile of SGN-CD33A, with TT patients having higher levels of drug exposure. Our findings suggest that the CD33 genotype can impact CD33 expression, PK profile, and trafficking of bound agents and thus may impact therapeutic targeting of CD33-directed agents.

Wang:Seattle Genetics: Employment, Equity Ownership. Rohm:Seattle Genetics: Employment, Equity Ownership. Biechele:Seattle Genetics: Employment, Equity Ownership. Means:Seattle Genetics: Employment, Equity Ownership. Thurman:Seattle Genetics: Employment, Equity Ownership. Arthur:Seattle Genetics: Employment, Equity Ownership.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal